~~Uniform Keyboard Piano~~

--and related innovations, from long ago to the present.

You're at: https://57296.neocities.org/ukbp.html (see also)

(last worked on: May 1st, 2024)

5/1/2024: I've been derelict of duty in not linking directly out to https://daskin.com/ --so here 'tis, and right at the top. Be sure to see Mr. Vandervoort's Frequently Asked Questions page and his YouTubes (which I did link to --below).

5/10/2022: Here, at Dodeka's defunct kickstarter web site, is what I thought to be too much to ask for --essentially: a "single row Janko" format keyboard instrument which uses reduced profile keys in order to preserve a decent hand span. Sadly, I see almost nothing about Dodeka that Googles up over the past year. Here's more, and more, and one more. This last seems (to me, at least) the most informed and even-handed criticism of a Dodeka style keyboard (and the one I proposed below). I appended it as text to this page because locating it on the website seemed tricky. I've included the URL.

* Just as western music and its keyboard oriented notation have grown up together, Dodeka and many others have offered alternative systems of notation to complete their alternative keyboards --nearly all of it in tempered 12 tones per octave. From reading the linked discussions, it seems obvious that at least the notes in Dodeka's notation (little dashes/rectangles) need elaboration and perhaps replacement --by more conventional looking notes --indicating their duration and association with adjacent notes.

Could one simply dismiss notation, play by ear and emulation --communicating what's been played through live performance, group/audience observation, recordings (video, audio and midi)?

* The rest of what follows was mostly written in ignorance

of Dodeka's instrumental offerings. Either I overlooked what was found

or it just didn't Google up for me. I did previously link to a page with

Dodeka's system of notation.

![]()

12/19/2021: I've also neglected to cite the relative

success of "Janko" type keyboards, as built, played and promoted

by Paul Vandervoort --here in his youth:

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cK4REjqGc9w

--and 28 years later:

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWCUnk9ABbM

* The discussions on and links from these YouTube web pages are most interesting. Here's one more, somewhat controversial URL:

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hJPCk1L4VWg

![]()

* It's my feeling that, given the same history and

promotion, "6-6" format keyboards (and maybe some type of an "all

white key" KB) would have fared better, since they "look" like a piano

and have mainly your "muscle memory" for the lateral dimension to contend

with.

![]()

11/27/2021: I've neglected to emphasize the good people

and their good works at "The Music Notation

Project" --who are ranging all over this field, including notation

in the context of uniform (6-6) keyboards. (Your

browser might caution "not secure" because the URL is "http" instead of

"https" at this point.)

![]()

5/20/2021: * Ms. Elaine Walker (at: http://verticalkeyboards.com)

rebuilds Roland keyboard instruments with reformatted keyboards. One of

her "microtonal" options is a "6-6" (ie: the KB looks like the above illustration).

I brought my page and its links to her attention, getting a thoughtful

and very hopeful response. This talented woman is working with a plastics

engineer to come up with a universal kit of alternative keys, so stay tuned!

![]()

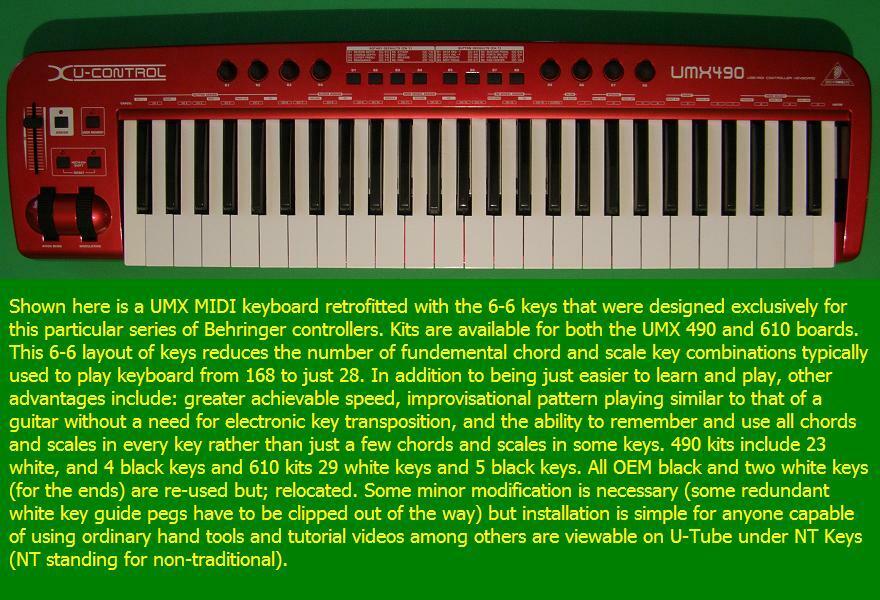

4/11/2021: * I found a kit for converting a Behringer

UMX610 midi controller into a Uniform Keyboard ("6-6") instrument --per:

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSWohfQUj-Q

> https://www.ebay.com/itm/263188863440#

* These devices plug into and use your personal computer in order to operate. Since the 490 and the 610, have been around for years, one wonders if they need updated drivers and applications in order to keep pace with our ever changing PC operating systems. I've seen one fellow's lament that his beloved 490 went haywire with the advent of Windows 8.1, so best find out if updated drivers are needed and available --before spending a lot of money.

* Personally, I've opted out of the update/patch/drivers merry-go-round. When my off-line XP-3 operated PC quits, I'll quit as well --reverting to a simplest/cheapest off-line laptop, word processor, printer and postage stamps. Consequently, I've decided not to acquire a MIDI controller KB, unless it has a "sound card" and can stand alone. (I believe Ms. Walker offers such an option.)

I'll also give more thought to an acoustic/mechanical

UKB piano (and see), but it's doubtful that can be

realized.

![]()

* 3/31/2021 update: * At:

> http://www.le-nouveau-clavier.fr/english/

--is the scholarly yet understandable presentation

I've long been hoping to find --by Ms. Dominique Waller (and in your choice

of several languages). I tried to send a "thank you", but her contact page

didn't seem to connect.

![]()

* Previously, I'd written to

several electronic musical instrument manufacturers, referring them to

Waller's web site and urging that they consider marketing a uniform keyboard

instrument. Besides Charles Wolff, I've written to:

Donner Musical Instrument Company, Yamaha Corporation of America, Casio

America, Inc., Alesis, Roland Corporation U.S., Kawai Musical Instruments

Manufacturing Co, Ltd., Kawai America, and even to Apple --which was the

only letter to draw a response: their form letter stating that they refuse

to entertain any and all outside ideas. (I've found that to be pretty much

the case for all corporations, with the old 3M company being an exception

--at least when it was still "Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing".)

![]()

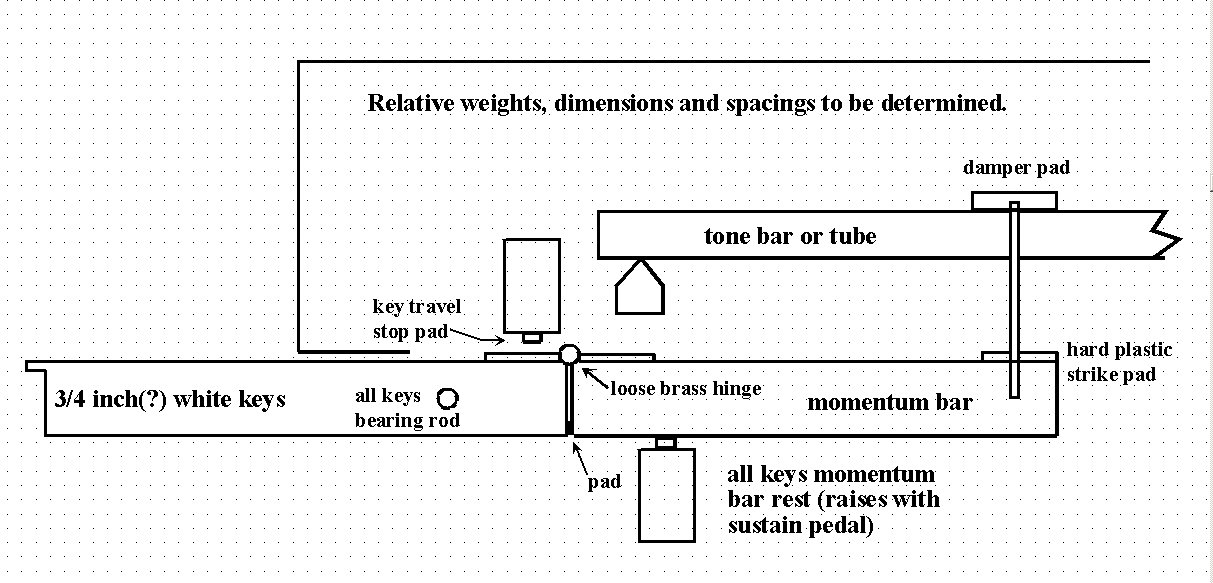

* Here are some ideas toward an

acoustic/mechanical piano --one affordable enough that it might-could enjoy

some popularity. For now I'll leave it to others to commission, venture

or DIY such an instrument. I can imagine it being a cottage industry production,

with sales of plans and/or kits for do-it-yourselfers.

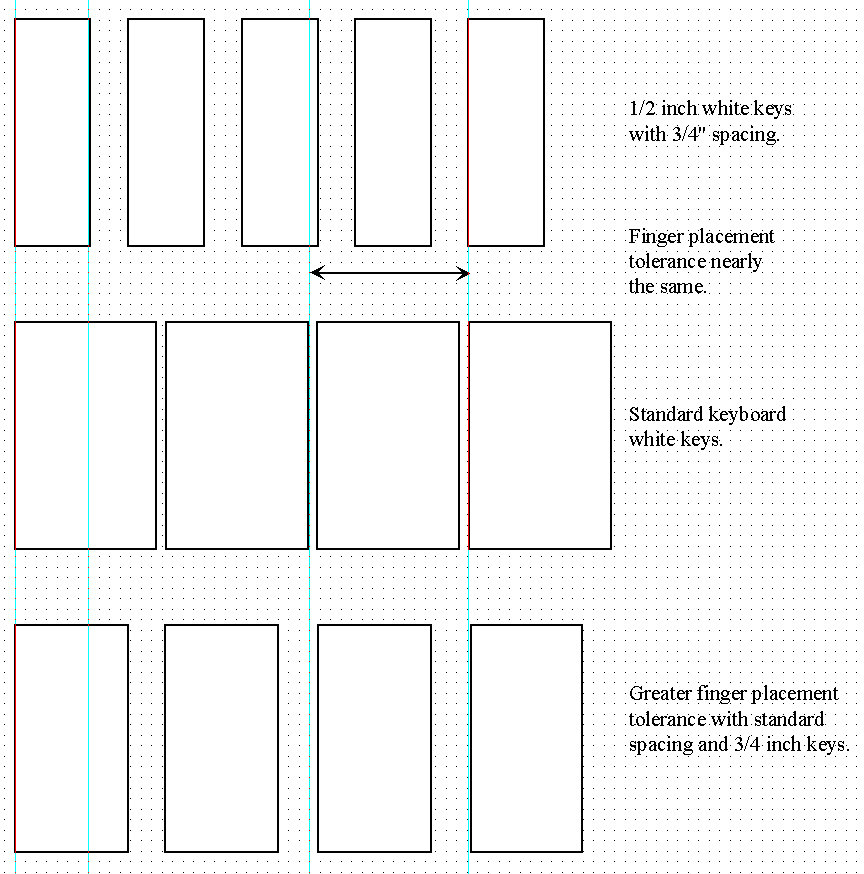

An all white key* piano with

1/2" wide keys and 3/4" spacing.

I suppose this is a UKB "xylopiano" or glockenspiel.

* Yes: this would be quite a break with tradition, but it's meant to be a better KB layout. (Sometimes one fails by timidly attempting too little :-)) (See the top-of-page 12/21/2021 update.)

~ Lightweight construction, rugged

enough for shipment by truck or trailer.

~ Kitchen cabinet grade finish

quality and appearance.

~ White keys only would simplify

construction and anticipate where KB music performance is

eventually headed. :-)

~ 3/4" spacing and 1/2" wide keys

would permit about an 11 key/tone hand span and as much white key finger

placement tolerance as does the spacing of a standard piano keyboard (which

would benefit if fitted with 3/4" wide keys).

* As suggested elsewhere on this page, one "fingering" per hand would then get chords and runs in all key signatures.

* My computer's keyboard allows 3/4 inch spacing with 3/16" between the 1/2" wide key tops. My hand calculator needs only 1/2 inch spacing. Serious initial production of UKBs (stand-alone pianos or MIDI controllers) would surely be electronic with a light touch.Be my guess that the follow-on production of concert hall pianos will also end up being electronic with adjustable key inertia ("weight"), force, drag, hysteresis and user stored preferences.

~ This piano should have a range

of at least 3 twelve tone octaves. (34 tone bars or tubes.) (7+ pentatonic

"octaves"?)

~ The open top sound output should

be adequate for a livingroom sized gathering of polite guests.

~ Instead of strings and a cast

iron frame, semi-permanently tuned bars or tubes (repurposed wind chimes?).

They'd stay tuned after the metal tone bars or tubes have been played for

a while and "work hardened". I'm guessing that the 1st and 2nd tunings

would be accomplished by moving small weights while watching an electronic

guitar type tuning aid (a frequency counter with musical notes read out.)

~ Seasoned or salvaged hard and

semi-hardwoods should be okay. The suspended tubes or tone bars wouldn't

require dimensional stability in the structural support.

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2rko4p9HaQg

In two minutes this pianist and his hand made piano

KB make clear the essence of all that follows on my web page.

![]()

* Through the past 200 years, individuals and music

interest groups have over and again reinvented and promoted various versions

of the uniform keyboard piano, mostly ending up with a home made prototype

to show for their efforts. See:

~ The Fukovo Balanced Keyboard.

~ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgGxyIhBZss&feature=emb_logo

~ The Bilinear Uniform Chromatic Kayboard.

~ The Balanced Keyboard --patents and examples.

~ and more below.

How long must we keep re-inventing and home building

UKB pianos before someone starts marketing one?

![]()

2/2/2021 updates: * Thanks to an old discussion at

Music:

Practice & Theory Stack Exchange, here's a suggestion that the

UKB format results in fingering difficulties:

~ "Every scale is one of two types, but every scale kind of sucks to play.

With the existing layout, every scale is different but most are easier

to play on their own than this. You'd have to play the first four fingers

and then cross your thumb over onto the second black note, or something

similar." (who?)

~ "I think you may have pinpointed the only real practical constraint - you either have to cross your thumb up onto a black key halfway through the scale, or cross after only two notes and then ALLL the way up to the next octave, neither of which sound very appealing." (Darren Ringer)

* I don't know how much music involves running scales,

but the relative ease and difficulties of most fingering challenges would

certainly impact the future of keyboard based compositions. Of course a

multitude of other fingerings would be facilitated. Again: however popular

the UKB might become, a goodly number of pianists would surely be encouraged

to play traditional keyboard pianos, to best render the world's existing

beautiful compositions. (me-Craig speaking.)

![]()

12/13/2020 update: * My e-friend Jerry has been telling

me about guitars (about which I also know little) --and how they can be

fitted with a "capo" across the strings behind an upper fret --in order

to play the same music --with the same chords/fingering --but in a different

key (a higher key, of course).

* That peaked my interest as to whether pianos have ever been "capo'd". Google quickly returned:

> https://pianofool.com/2016/03/how-to-capo-your-keyboard-attn-guitar-players/

So yes. Higher end electronic pianos have a "transpose button", such that the same key of C fingering can be used in any other key --!

* That does have a performance drawback, per:

> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROkIYFp5V-Q

--and the ease of such transpositions raises a question: does it obviate any past need for a uniform keyboard?

No. Per that last YouTube, the T button doesn't allow

you to change key signature gears on the wing during a performance, whereas

a UKB would facilitate such modulations, while obviating the need of a

transpose button.

![]()

I've found the following pronouncements concerning--

--The nature of music that's played under various

key signatures.

French composer Charpentier in 1682:

C major - “obscure and

sad”

D major - “joyous and

very warlike”

E flat major - “cruel and hard”.

According to Skinner (Ernest? James Scott?):

C major - bold but piercing

A minor- sad and plaintive

G major - plenty of body

E minor - sterile and thin

D major - splendid body

A major - The Fiddle Key

F# minor - exquisitely harrowing

E major - brilliant but lacking in body

F major - thinnish

Bb major - velvet, very rich and fine

Eb major & C minor - weird, fascinating and beautifully

sad

Elias Howe in 1870 (not the sewing machine guy)

C major - warlike and well adapted to martial

music

G major - gay and sprightly and (versatile)

D major - grand solemn melancholy

A major - plaintive but lively

E major - same as A major

F major - sober thoughtful (best for the violin)

Bb major - same as F major but more plaintive

Eb major - similar to A major but more sweet

Aside from the above contradictions, consider that:

* Previous to 1926, when "A" was informally standardized at 440cps in the United States (that only went ISO in 1955), the absolute pitch of any note was peculiar to the nation, culture or city in which it was played.

* A tuning fork that belonged to Ludwig van Beethoven around 1800 (now in the British Library) is pitched at A = 455.4 cps --well over a half-tone higher than today's 440cps. Possibly, long and hard use (for Beethoven grew increasingly deaf) affected the fork's hardness or temper.

Towards the end of the 18th century the frequency of A (above middle C) ran through a range from 400 to 450 Hz.

* Be my guess that melodic mood owes much to the "modulations" (note sequence shifts) within a piece of music, and little or nothing to the absolute pitch of that "first note"/"tonic" of a key signature.

Different key signatures probably have some utility

in facilitating the fingering of particular pieces of music, given the

need to weave around the blacks and whites of a standard keyboard instrument,

but with sprinklings of such as "accidentals", "melodic" minors, "flatted

7ths", "minor thirds", the multiplicity of key signatures seems (to me)

a needless tangle.

![]()

Tentative conclusions:

* It increasingly seems (to me) that, despite the ease with which the uniform keyboard would allow a piece of music could be transposed from one key to another, the only point in doing so seems (to me) to accommodate the range of a vocalist or another instrument.

* If an "all white key" UKB piano is to be pursued (perhaps as a switched-to mode on a standard or black-and-white key UKB), I suggest biting the bullet on hand span and using standard sized white keys, which would allow the same fingering for a score that's shifted to any "key".

* Hopefully, playing a piano would become more intuitive, easier to learn for new students --leading to a more democratic route for the popular expression and creation of instrumental music in general --more like singing and whistling, to which we give little effort or (logical) thought.

* Studies, experts, scholars, authorities and priesthoods are fine, but "the people" might also lead --with musical "free speech", given a more accessible structure to climb and build upon.

* The potential effect on musical notation seems salutary.

Others

have worked on simplifying the scoring of music. One obscure

system actually addresses a uniform keyboard.

![]()

* Traditional terms like a "fifth"

seem a barrier to would-be musicians getting a foothold on understanding.

The great advantage of web pages is that they can be linked to a ready

explanation (as practiced in Wikipedia articles). Possibly, new terms should

be adopted --but I'm too much out of my depth to more than hint at a few.

* The following coherent description of music basics is from Microsoft's® Encarta® Reference Library 2005. © 1993-2004.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~quotes:

Tuning Systems, Musical, theoretical or practical

systems for determining the correct tuning for the intervals of a scale.

Because some leeway exists within which the ear recognizes two notes as a given interval, cultural concepts of “correct” pitch and intervals vary; for example, intervals of 200 cents, 204 cents, and 182 cents are all heard as whole steps (1200 cents equals one octave).

In strongly concordant intervals, the sound-wave frequencies of the upper and lower notes form simple mathematical ratios, such as 2:1 (octave), 5:4 (major third), and 3:2 (fifth). This last ratio, the “pure” or “natural” fifth, is the basis of Pythagorean tuning, used in ancient Greece, ancient China, medieval Islamic countries, and medieval Europe. Tuning a series of fifths, beginning on F, produces the seven notes of the C-major scale, F C G D A E B, then the five notes F# C# G# D# A#, and finally E# and B# (theoretically identical with F and C, hence the term circle of fifths for this series). The Pythagorean B#, however, is slightly higher than the initial C, making the system unusable on fretted and keyboard instruments; moreover, the thirds, sharper than the natural third, are strongly dissonant. The system works best for unharmonized melodies, sung or played on a violin or other instrument of adjustable pitch.

In just intonation, some intervals are derived from pure fifths and others from pure thirds. Mostly a theoretical system, it produces euphonious chords but has serious disadvantages, including an important out-of-tune fifth (D-A).

From early times, these ideal scales were tempered, or slightly adjusted, when fretted and keyboard instruments were to be used. In mean-tone temperament, popular during the baroque era (roughly 1650-1750), several series of four minutely flattened fifths result in pure major thirds in the most commonly used parts of the C-major scale. One seldom-used interval (D#-G#), called the wolf, is always out of tune. Except for special effects, musical modulation (change of key) is limited to keys closely related to C major. As late 18th-century musical styles developed, musicians became more interested in equal temperament, a system that was adopted only gradually—by 1800 in Germany and by 1850 in England. In equal temperament all fifths are slightly flattened equally, so that B# is in tune with C as the circle of fifths is completed. The major third is somewhat sharp, within acceptable limits, and modulation to all keys is possible.

Pentatonic Scale:

This is a musical term for a scale of 5 notes, equivalent

to the black notes on a piano and their transpositions. Found as early

as 2000 BC, the pentatonic scale is common in folk music from America to

the Celtic in Europe to China.

![]()

* There's a special person: Charles

Wolff --a musician who's been building replicas of classic clavichords

and organ keyboards for 25 years. He's open to ideas and is interested

in uniform keyboards. See his web site.

If you're in a position to invest in (and invest yourself in) a custom

built clavichord^, Mr. Wolff will be glad to discuss its details with you

(which might well be at considerable departure from what's on this page

--your choices).

^ The clavichord is a highly regarded, piano-like instrument (its strings are struck), but with simpler action and brass blades ("tangents") --instead of felt lined and weighted hammers. As such, it is graciously quieter than a piano and notes are expressed/sustained a bit differently. Importantly: clavichords are more compact and far lighter in weight than a mechanical piano --since the artist must take his/her unique keyboard along when traveling.

^ Most early clavichords economized on size and string

counts by having their keys raise frets, thereby precluding the polyphonic

sounding of certain combinations of notes --which strikes me as a bad compromise.

Unfretted clavichords are larger and heavier but (of course) an all "white

key" UKB would again reduce the string count --along with a reduced octave

range.

![]()

* At this

music venue we read: "Another trick that might appeal is re-mapping

the notes of your chosen key/scale to the white keys of your MIDI keyboard,

for ease of playing. Having made your key/scale selection, simply adjust

the MIDI Modifier’s Transpose setting up/down (either by trial and error

or by working out the number of steps required) to settings that get the

majority of the notes mapped onto white keys. As a simple example, if a

song is in Bb major, the scale contains Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G and A. If we

set a Transpose value of -2, Bb notes will actually be played on the C

key and Eb on the F key. All the other notes are also transposed by two

semitones, but they remain on white keys. This can be made to work for

many common scales, including major, harmonic minor and pentatonic, although

some (eg. the melodic minor) will have one or two ‘correct’ notes mapped

to a black key. With Transpose To Scale active, though, the plug-in will

pitch-correct for you if your fingers miss the occasional black key."

* Well Hallelujah! There's finally an electronic/digital keyboard instrument with remap-able/reassignable keys.

* Still: who wants to take a deep dive into digital

technology to do that? Let's instead "Google" around for a compact, perhaps

an analog (ie: with physically tunable strings) piano, clavichord

or harpsichord.

![]()

* We wait upon some brave venture

capitalist to invest in a UKBP project --which should be an affordable

and simple digital piano KB with standard sized keys. To cover both possible

outcomes, it might be built with a black-white-black-white run of keys

(per the above illustration), but include a switch to enable a reduced

gamut of white-key-only chromatic octaves.

Another approach would be to field existing lines of

digital pianos with standard KBs, but add a chromatic scale switch for

the white keys. If successful, however, that would pretty much preclude

acceptance of a black-white UKB.

![]()

* Jon Brantingham 's web site explaining the structure

and vernacular of composition --so very much anchored in tradition, is

(IMHO) excellent. This subject is so dense as to numb the mind and defeat

one's enthusiasm for creating music. It needs Jon's expository skills.

(more)

![]()

* Musical structure and notation.

Just as some restless students of music look at a keyboard and wonder if

it needs to be such a challenge, others (sometimes those same people) cast

a gimlet eye at the traditions of notation.

But: where to start? How can I see the whole of it?

* The "warp and woof" of (at least "western") music is (and I'm open to corrections on any of this): rhythms, melodies and agreeable ("consonant") harmonies --struck between pairs of notes and chords (perhaps 3 notes, representing a pair of such pairs and a shared note). Achieving harmonies across the span of several octaves (or doublings of a given base note's frequency) has been a somewhat crazy-making mash-up of historical progress --leading to what we now work with: a "tempered" chromatic scale of 12 steps/notes per octave.

* Although history traces approaches to equal temperament as far back as 1496 (Franchino Gafori), even Bach's "Well-Tempered Clavier" (1722) stopped a bit short of equal scale steps. Some say that fully orchestrated/accomodated equal temperament didn't really get nailed down until late in the 19th Century --!

* I was surprised to learn that ancient systems of diatonic tuning produced such contradictions and dissonances in step widths --that some pairs and triads that we hear today were simply abandoned.

* Here's a guitar oriented discussion that addresses similar issues in musical theory:

** It does seem that the best compromise for smoothing over problems of disonance --is the fully tempered, 12 equally stepped notes of the chromatic scale. But I've wondered if --given those ideal diatonic tone ratios (3:2, 4:5, 5:3), there might be a "lowest common denominator" number of notes in an octave --which would perfectly satisfy them all. (Hmmnnnn). (But: I suppose the 12 note chromatic scale is plenty gudenuf.)

^ Heinrich Hertz was a brilliant scientist, worthy of honor --but I don't like to use the opaque term "Hertz", in place of cpm/cycles per second, kilocycles, megacycles, and etc. Some honorific terms/units seem agreeable, like (Michael Faraday) "Farads", in place of Coulombs per Volt, or Joules in place of Newton-meters.

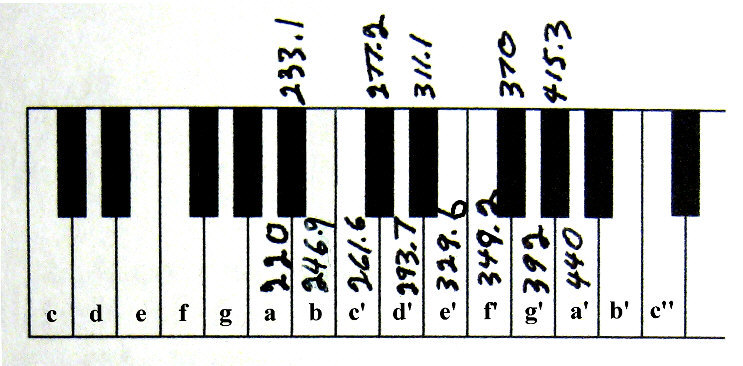

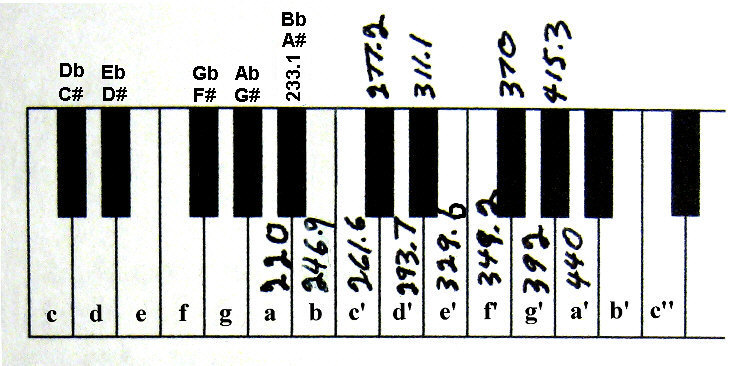

This standard keyboard layout is reaching for consonance/agreement when striking (say) a "fith"^ of c' and g' together: a ratio which "wants" to be 3 to 2 (3:2), but is "tempered" at 392/261.6 = 2.997etc --to 2 --and that's close enough. Similarly: a "major third" (c'-e'), wants to be 4:5, but is 3.974 to 5; and a "major sixth" (c'-a'), wants to be 5:3, but is 5.046 to 3.

^ I read that such terms as a "fifth" harken back to the Pythagorean (ancient Greek) understanding of music (ie: "the tone of a plucked string held at the 2/3rd point is a fifth higher". They used diatonic scales (thought not to be troubled with attempts at harmony) and at one point (some say) even worked out a 12 tone chromatic scale.

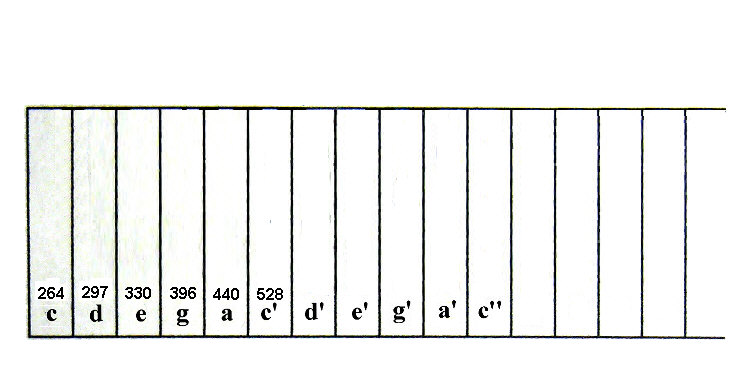

* To be clear about these intervals, here's a lay-out comparing diatonic with tempered chromatic scales:

Scale notes named

Do Re Mi Fa

Sol La Ti Do'

Re'

Notes played

C D E

F G A

B C' D'

An Octave ratio in key of C

1

2

A Major triad ratios in key of C 4

5 6

(8)

A Major triad ratios in key of F

4 5

6

A Major triad ratios in key of G

(3)

4 5

6

Diatonic scale cps

264 297 330 352 396

440^ 495 528 594

~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~

~~~ ~~~ ~~~

Diatonic frequency ratios

9/8 10/9 16/15 9/8 10/9 9/8

16/15 9/8

8 tone diatonic scale intervals

whole whole half whole whole whole half whole

Tempered chromatic scale cps

261.6 293.7 329.6 349.2 392.0 440.0 493.9 523.3 587.4

~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~

~~~ ~~~ ~~~

Tempered frequency ratios

2-6 2-62-122-6

2-6

2-62-122-6

^ There's an international agreement that "A" is 440cps.

The disparities 'twixt diatonic and tempered chromatic scale frequencies are widely considered to be negligible. I've read that it would take 72 notes per octive to sound all chords diatonically.

* Could it be that the whole scheme of western music

has gotten off on the wrong foot, historically, and is preventing some

delightful music from emerging? If so, any remedy would hopefully preserve

the vast range of inspiring music that we have in hand, to remain familiar

and playable. (I'm a long ways from coming to conclusions about music structure.)

![]()

![]()

Other systems of music --Pentatonic

and such:

* I suppose it behooves me to think about and listen to systems other than diatonic and chromatic. Perhaps I can find such studies already credibly done. If so, watch this space for link-outs and comments.

* It so happens that the Pentatonic scale^ in F# skips nicely along the black keys: F#, G#, A#, C#, D#.

* But yes: by using the 12 tone scale and a standard piano, there be 12 key signatures to deal with --fingering in and out of the black keys --! Obviously, an all white keyboard (by half tones) would allow the same fingering for all key signatures, but with limited hand span (so arpegiate).

* Do we need 12 key signatures? What if: all music was transposed into C major and C minor --which minor (of course) uses the same keys? What if: all those keys were white --and the other keys were eliminated? (See "BS")

> https://www.dodekamusic.com/alternative-music-notation/

![]()

* Here's an interesting pair of

quotes from the comments section of Jon Brantingham's excellent

web

site (from which videos and PODcasts are linked out as well):

> Manuel: "I think the difficulty associated with music theory lies largely with the design of the piano keyboard and the 5-line staff, which are essentially designed to make the C Major scale easy to work with, while screwing up every other scale. The Janko keyboard (an isomorphic keyboard) would have made things easier, because chord shapes are all the same in every key, so even individuals with no musical training can quickly spot logical patterns. There exist alternative musical notation systems (e.g. 3-line Muto notation) that closely mirror the isomorphic layout and completely remove the need for key signatures, accidentals, sharps, and all that nonsense."

> Jon: "Great points Manuel, but you also have to realize that the system, clunky as it can be, has still allowed the creation of amazing music and amazing performers of that music. I've looked into other kinds of notation, but I came to the point that it is not worth my time to learn them, and just to focus on traditional music theory and notation.

That pretty much sets the "tone" for the above and

all which follows. While we sure can't expect Jon to start over, younger

others might wish to check out alternatives --hopefully, with even-handed

guidance from competent and fully informed older others (which leaves me

out, of course).

![]()

* Many alternative

keyboard schemes have occurred to those of us who've struggled to master

the fingering of chords and melodic runs in different key signatures. As

to uniform KB designs: "Mr. Southgate concludes

as follows: 'If music were in its infancy, it would doubtless be possible

to design a more convenient keyboard than the one we now possess.

But the art is too old for such an alteration. For the modern keyboard

and the tonal divisions of the scale which now constitutes our alphabet

of sounds, the great masters have written their piano and organ music.

It is hardly likely that we shall accept a new system, however convenient

it may be for the fingers, or delightful it may appear on paper to the

mind of acoustical mathematicians.' "

* First off: existing pianists should be accommodated with traditional keyboards --forever. We're talking new students of old and new music. No doubt some old master pieces would be more difficult to play on a revised keyboard, while others would be easier, but what intrigues me is the potential for new music, the novel expression of old music, a significant increase of popular interest in music, those who can play and create it --along with boom times for the manufacture of keyboard instruments.

Here's Joseph Clay Saltsman's 2006 patent description for a left-right symmetrical, uniform keyboard piano:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"A 2 manual musical keyboard with the pitch progression

on one of the manuals reversed. The keys on these manuals are segregated

into 2 groups of 2 different heights in the same way as a standard musical

keyboard. The key configurations on these manuals have 12 semi-tones linearly

distributed across 12 keys of alternating heights. Instead of the traditional

7 lower keys (white) and 5 upper keys (black), this arrangement has 6 lower

keys and 6 upper keys. The notation system for this unique keyboard is

a dual character set. Six unique characters for the upper keys and six

unique characters for the lower keys. The musical staff for this unique

keyboard will have six lines assigned to one character set and the six

spaces assigned to the other character set." followed by: "In application,

it can be seen that the scale fingering for this system is very simple."

(Patent #7253349)

* And here's

Mr. Saltsman's YouTube video. He makes the advantages of a UKB very

clear and might well be reaching more interested people than all pre-YouTube

efforts combined. (Well done!)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I've Googled up 3 excellent overviews of the uniform keyboard idea.

* Bart Willemse's "Balanced keyboard website" at:

> http://www.balanced-keyboard.com/

--where you'll find UKB rationales, histories of alternative KBs and even

electronic piano model specific DIY suggestions for building your own UKB.

* For an excellent run-down on the rationale of the scales,

chords and musical structure behind the UKB and its alternatives, see Jose

Sotorrio's web site: "The Bilinear Uniform Chromatic Keyboard (BUCK)" at:

> http://migo.info/index_en.html

* I especially liked the historical references at Dominique

Waller's:

> http://www.le-nouveau-clavier.fr/english/

--where we learn that this type of uniform KB layout

(6 white keys and 6 black keys over three rows) was first proposed in 1654

by the Spanish prelate Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz (a correspondent of Descartes).

![]()

* Back in the 1960s, while trying to get through a

lessons book for beginners at the piano, I decided: "this is nuts!".

I tried to figure out just what was wrong --and then what to do about it.

That resulted in imagining a black-white-black-white "uniform keyboard

piano" layout plus some altered musical notation to go with it. Thanks

to the U.S. Navy, I was briefly stationed near and visited the Patent and

Trademark Office, where I was treated most cordially and at no cost. Pages

(workers who help with patent searches) brought me wicker baskets full

of cards bearing granted patents, some of them reaching back into the 19th

Century.

And sure enough: they turned up a 100 year-old patent which nicely described my keyboard layout (see the top illustration on this web page) and its advantages --but in the form of a keyboard overlay for a conventional piano. That invention (as I recall) was being patented by an American branch or representatives of (something like) the German "New Keyboard (Neu Klaviatur?) Society".

That overlay idea should have been key to advancing the UKBP, since it eliminated the necessity of artists traveling with a full sized UKB piano (and a piano tuner). The overlay would have been heavy, but of about the same bulk as a modern, full featured electronic piano.

~ I can't find my old notes and I've been unable to turn up current references to that German society's keyboard overlay, but I have found what appears to be exactly the same idea in a 1962 patent (filed in 1957) for just such an overlay: "--the provision of a set of over-keys being superposable upon and removably attachable to the keys of a conventional piano, and being adapted when so attached to provide a keyboard consisting of alternate black and white over-keys, each being effective when pressed to produce a tone one half-note different from that produced by either of the two adjacent over-keys".

~ An 1874 patent by Francis Cramer describes an intact, black and white key, uniform keyboard piano and its advantages --to the extent of anticipating Chesters' (see) 6 line staffs and their advantages.

~ An overlay UKBP idea was patented again in 1968 as a "Uniform Keyboard adapter" by Willis H. Thompson, Jr.

~ Also, there's an interesting 1949 patent by John Robbins for going with (rather skinny) all white keys (or appropriately colored, if desired), glued down onto a standard keyboard.

~ Finally: here's an amazingly detailed

1987 proposal for new musical notation^ and a co-ordinated uniform keyboard

to go with it: a "Graphic Music System" by Thomas P. Chesters:

> https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/55/ec/2e/88ddc024cb3bfa/US4885969.pdf

^ A 6 line staff is used, with spaces corresponding to white keys and the lines to black keys --no sharps or flats are needed.

Mr. Chesters' great efforts ended up abandoned (at least as a patent) for lack of a PTO maintenance fee payment. I Googled up his name and his project but found nothing across the Internet.

~ Wikipedia's article for the "Jankó keyboard"

(1882) lists several patents that I've not yet explored.

![]()

* For 55 years I've been abstaining from playing the

piano, "saving myself" :-) and my reflexes for the UKBP --upon

such a time as when I'd finally get around to building one. (At 77 years

of age now, maybe I should give it a whack?)

As to finalizing a UKB design of my own:

* Stupid question: is using black keys worth our hands being able to span an octave plus (12 to 14 half-tones)? There's a downside in that two fingerings (four, if you count both hands) might be required to transpose a piece into another key signature. Of course, without sufficient span, much existing music would be unplayable --except by adaptation/arpeggiation, so let's consider John Robbins' solution.)

* How important --to getting a tactilely sensed hand location and purchase upon the keys --are those elevated black keys? Would trapezoidally profiled, white-only keys satisfy this need? Should certain keys also be textured? (see)

* The standard keyboard is quite compact, with generous key spacing and width:

* We own a novelty electronic piano (an old Casio SK-1). Its white keys are spaced only 11/16 inch (17.5mm) apart and my hand spans 11 of them.

* Were we to place white keys (and white keys only) into the space traditionally allowed for an octave's span of 12 tones (6.56 inches), the keys would have to be only 0.547 inch wide (13.9mm) --minus the gap --so say: 1/2 inch (12.7mm) keys. (see)

* A standard computer keyboard's slightly trapezoidal keys are spaced 3/4 inch apart, with 3/16" of clearance between their top surfaces. Many of us find this right at the limits of our "fat fingered" frustration, but the traditional elongated shape of piano keys should help a lot. (The exact shape and spacing of a piano's keyboard must not be a casual, hit-or-miss decision!)

* So, and tentatively: I'd either go with a black and white UKB --which would actually allow of slightly wider (than standard) keys and/or gaps (while preserving the standard octave distance), or: bite the bullet on white (only) keys, spaced 3/4 inch apart, for a 9 inch octave span --which would be one key too far for me (and see).

* Just off (my ignorant) hand, I'm inclined toward leaving the white keys white and (if used) the elevated keys uniformly black, rather than to be painting UKBP keys as an echo of those on a standard keyboard. Perhaps a clean break with old key signatures and associated notation is in order. New scoring for old music would be in order (and see).

* And for our digital era:

This link leads to a significant Japanese effort and web site, wanting to sell us their Chromatone keyboard pianos.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you remove the "front panel" of an upright piano

and look how the keys continue after the part that is black and white,

you'll see all of them having wooden levers of the same width. The black

keys are basically right on top of the levers, the white keys flare out

in some pattern such that there are seven equispaced white keys per octave.

Obviously it would be [easy] to just extend every lever into a single centered

key like the black keys already are.

The Jankó piano does something similar but staggers the keys into two rows (and duplicate rows) to better match the realities of playing intervals to two hands.

This hasn't caught on. If you try playing a scale, or a sequence of thirds in a diatonic scale, you'll understand why. A sequence of thirds played in a single hand would not really work in a one-row arrangement if you had to play it legato. And it would end up a nilly-willy sequence of minor and major thirds in some strange pattern: the inherently diatonic nature of most Western music is not a nice match to a uniform keyboard layout.

One area where uniform keyboards have taken off to some degree are chromatic button accordions that have a uniform layout with three staggered rows of buttons (and possible repeat rows). Here they allow a much better match of the space requirements for producing a note of a given pitch to the space taken by a playable keyboard. For a wearable instrument, they are able [to] provide a much larger range than possible with a piano-style keyboard, and since there are no key dynamics (the buttons only open valves while the dynamics are mostly created with the bellows), the much more compact hand shapes are not impacting the ability for dynamically balanced play.

In ensembles playing from score sheets, the difficulty of sightreading polyphonic scores in the usual diatonic notation for such a uniform keyboard makes for a lot of players choosing piano keyboards in spite of the technical advantages of a button keyboard. In countries with a folk music accordion tradition, CBAs fare better since playing them mostly monophonically by ear while adapting to the key of other players is similarly [as] natural as it is for string instruments that are sort-of uniformly playable (fret/fingering distances decrease with higher pitch, of course). Outside of folk music traditions (and very ingrained instrument cultures like in Finland and Russia), the CBA tends to be an instrument mostly played by soloists where the possible gains in technical achievements more than offsets the additional hurdle of learning to map diatonic music and notation to a uniform keyboard layout.

So while an instrument exactly like you envision is not readily available, it would be easy to build. However, experience both with pianos and with other instruments makes apparent that it would not end up an option attractive for actual playing.

Even if you look at instruments like recorders, flutes and other woodwinds, the basically arbitrary key/hole/control arrangement of a monophonic instrument is patterned after diatonic scales. That even holds for comparatively "newfangled" instruments like saxophones or ophicleides (the latter being a brass instrument, of course).

Jan 13 (2022) - by "user84931" at:

> https://music.stackexchange.com/questions/120281/could-one-make-a-piano-with-all-notes-placed-on-narrow-white-keys

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

![]()

My best shots at defining musical

jargon (including my own).

~ Fifth (5th): The span of an interval between two ascending or descending tones which, when sounded together, produces an agreeable consonance (ie: they sound "right", with little or no hint of clawing, askew beat notes) --such as the musical notes "C" and "G". The frequency (cps = cycles per second = "hertz"), the frequency ratio of these two tones is 3 to 2 (3:2) or 2:3. What makes them click for us is that the 2nd harmonic (or doubling) of the higher tone matches the 3rd harmonic (trippling) of the lower tone. Even though the source of these tones might be purely the sine wave fundamental tone only, non-linearities (rattle) in your ears develops these harmonics anyway.

Many ancient musicians and their societies discovered

such paired notes, often making up a musical scale by tuning them all or

just some of them onto the same instrument. When using the 12 ("half")

tone ("chromatic") system of music, it works out that a 5th spans 5 tones.

![]()

Musical Keyboards & Piano mfgs.

Donner Musical Instrument Company

RM 1501

Grand Millennium Plaza (Lower Blk)

181 Queen's RD Center

Hong Kong <donnerdeal@gmail.com> (wrote:

January 29th, 2021)

~~~~~~~~~~

Yamaha Corporation of America

6600 Orangethorpe Ave.

Buena Park, CA 90620 (wrote: January 4th, 2021)

~~~~~~~~~

Casio America, Inc.

570 Mt. Pleasant Avenue

Dover, NJ - 07801-1620 (wrote: December 17th and

20th, 2020)

~~~~~~~~~

Alesis

200 Scenic View Drive

Suite 201

Cumberland, RI 02864 (401-658-5760) (wrote:

Februrary 14th, 2021)

~~~~~~~~~

Roland Corporation U.S.

5100 S. Eastern Avenue

Los Angeles, CA - 90040-2938 (323-890-3700) < > (wrote:

February 26th, 2021)

~~~~~~~~~

Kawai Musical Instruments Manufacturing Co, Ltd.

200 Terajima-cho Naka-Ku

Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka-Pref, 430-8665

Japan (wrote: March 7th, 2021)

Kawai America

2055 E. University Drive

Rancho Dominguez, CA - 90220 (copied: March 7th, 2021)

~~~~~~~~~

Next up: Apple (best address yet to be determined)

![]()