So: You've got a digital

camera :-)

(last major revision: 12/19/2003,

last worked on: September 28th, 2022) (Go to

Trim-02

for working with a Fuji W3)

See

here first.

You're at: https://57296.neocities.org/trim-01.html

fastfind>>> composing

pairs, the basic image, film

scanning,

(On to Trim-2)

How to turn Fuji-W3 camera images

into stereo prints: step-by-step -

3/20/2022: The short version of these digital graphics

pages: give it up --unsustainable! The digital world never rests. Your

computer, your applications and your precious skill sets will soon be obsoleted

and unsupported. Read on at your peril. See also Microsoft forums for installing

and running legacy applications on Windows-10. You have to start by stopping

the setup.exe autoplay and option Properties\Compatibility for the install

file --then maybe again for the application itself.

(6/28/2020): There use to be several web sites where

you could download PPub in the last version #10. Possibly this is a limited

"CE" (or some such) version, but it allegedly installed and ran well on

Vista and Windows-7. (Be sure to enable Windows XP legacy mode/s.) (Update:

These old programs won't install correctly on a 64 bit operating system

without taking the right "Properties" options before running the install

["setup.exe"] file.)

* The full Pro version was once available through Amazon.com

(you might wish to read the customer reviews) and it still might be available

used. (Last seen at:

http://www.amazon.com/Corel-PP1L10ENG-PICTURE-PUBLISHER-PRO/dp/B00005Q5IM

* I use the ancient PPub-3.1 and PPub-8 versions, which

both ran at least until the XP-3 operating system.

* A good general purpose graphics program has been

a free download: "Paint.net", but the web site looks a little fishy to

me lately.

http://www.getpaint.net/

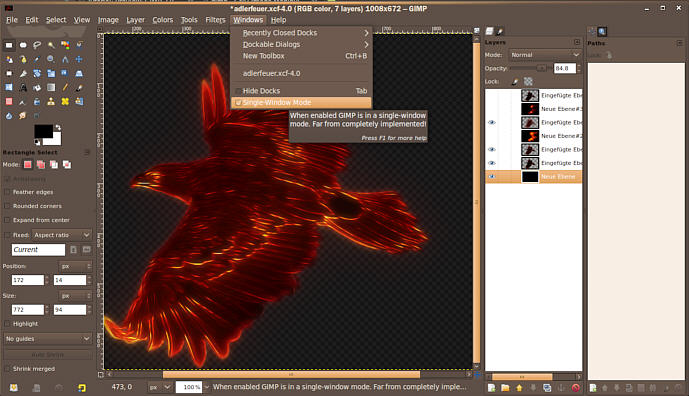

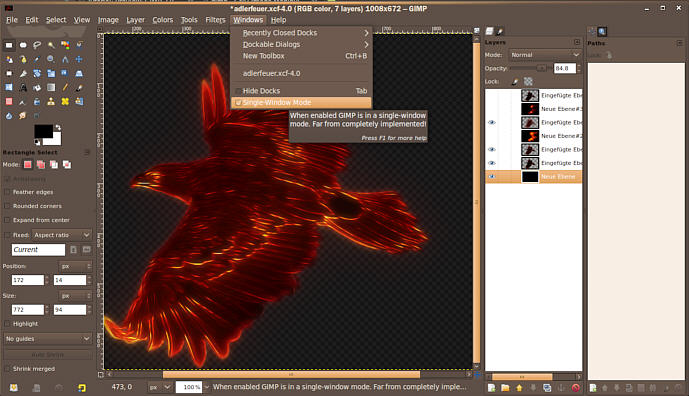

* Another option is "Gimp". This is written for Linux

operating systems and the authors/home site appears to take no responsibility

for how others might port it to Windows and MacIntosh. I've got good reports

about its performance under Windows-7 (and presumably on earlier Windows

systems) in version number 2.6.8. (You don't want 2.6.9) --but: when I

tried to use Gimp it gummed up the works in my PC.

The following image is what version #2.8.0 will (optionally)

look like.

Get it via: http://www.gimp.org/downloads/

See the "Working With Digital

Images" page for programs which are made for working with stereo images.

File Management (for

paired digital cameras):

1) Label one of your cameras "Left" or "Right" and

use it in that position.

2) Typical digital cameras (say: a pair of Sony DSC-P71s)

has an internal clock and conveniently assigns each image file the time

of day --to the second. Don't expect your cameras to keep the same time,

simply reset the faster one (occasionally) behind the slower one. After

each shoot, when you "debrief" your cameras --transferring their memories

to your hard drive, note the current time difference. Create a simple text

file (say: with Microsoft's "Notepad" or "Wordpad" programs) which bears

the name "Rt-__sec-faster.txt" --or some such, then save it to the directory

(or: "folder") for the right camera's images. (See the example highlighted

file in the lower right of the following image.)

This is a screen-capture of the file manager program "Servant

Salamander" (which was still a free download, last I checked). It's the

nearest approximation I can find of the terribly missed and long lamented

"Windows File Manager" program --which we enjoyed using under the old Windows-3.1

operating system. (It appeared to be identical with the even older DOS/GUI

"Central Point File Manager" program --presumably bought out, then shit-canned

in favor of "Windows Explorer".

[We've since set our cameras such that the their clocks

are well synched, but their frame numbers are way different and continue

to diverge. Then we put the frame files together in the same folder/directory,

bringing the pairs together via a "by time" sort.]

My wife Peg runs the left camera, I (Craig) run the

right camera --unless just one of us is tripping both cameras (when they're

mounted on the short bar).

Note the two highlighted image files. They're obviously

a pair.

** Alternatively: If your cameras permit of the frames

being serially numbered --spanning chip erasures (as do Sony cameras),

then let the more heavily used camera get well ahead of the other --such

that there's no danger of one camera's output over-writing the others in

the same folder (directory). If you keep your camera's clocks well synched,

the left and right frames will line up together (when sorted by time).

(For cameras that assign time based file names to frames

--or for cameras which number each series of exposures from "#1", then

(obviously) you must use a side-by-side directory display --per the above

example.)

* That "DS4" file is from my Micrografx "Designer"

program (version 4.1 here) which I use to composite all of my printer-ready

pairs onto virtual card mounts. You might wish to get a similar "Designer"

type program in order to make "monolithic" (one piece) view card printouts.

I have despaired of creating a tutorial because it will be obsolete (with

respect to the devil's dance of revisions in graphics programs) by the

time you happen across it. Instead, I'm offering old fashioned "trim and

mount" steps:

t-plate-steps.htm

--done with an exacto knife, mat board mounts, and

some kind of adhesive (say: double stick tape).

* To prepare the pairs, I use Micrografx "Picture Publisher"

in two versions: 3.1 and 8.0.1. Version 8 seems to still be good enough

to keep up with the graphics world's new formats, but it has crummy auto-masking,

will annoy you with it's non-alphabetical file formats list, will try your

soul by suggesting that you've modified an image file when you haven't,

and then there's the need to constantly deal with combining "floating objects"

--so: my heavy lifting, first run graphics program (working 24 bit RGB

TIFFs) remains version 3.1, which I bought new in 1993.

** Version 3.1 is the best thing Micrografx ever put

out. It cost me nearly $500 in 1993, and that was a big reduction from

its 1992 price of $800. It beat the pants off of Adobe Photoshop, it melds

perfectly with Micrografx's Designer-4.1 (another big chunk of cash at

the time) and remains tops for graphics scut work to this day. It won't

handle the newer JPEGs (which I convert to TIFFs anyway) and some of its

advanced features (like algebraic photo pastes, which I used for making

anaglyphs) are lamed when run under in today's operating systems (at least

up to XP-3 --and Vista on up seem to be a no-go for this old 16 bit program).

PPub-3.1 treats masking differently in that you work

with outlines ("arcades") which describe objects that you can subsequently

move copies or cuts of in a very controlled, even calibrated way.

* I tried to determine if this work can be done with

"Paint Shop Pro-7", but by the time I was working on an approach, out came

the much changed version #8 (then 9, then the 48 bit 10, then all of it

apparently abandoned by Corel) --so my tutorial screen captures and techniques

would have been obsolete from the get-go. I've also tried editions of Adobe

Photoshop (which product seems to have taken a hit in its "elements" version),

the excellent, well designed (and affordable) 48 bit capable program "Picture

Window Pro 3.5", and even the Russian "Picture Man 5".

Earlier I tried Corel's "Paint" (sunk months into that

one) and half-a-dozen lightweight graphics programs.

Sometimes I think about having a now ancient 486-DX

based computer specially built for me that will run under Windows-3.x (which

I tried doing once, but the old computer tech's wife died and he went to

pieces).

The

basic image:

Set your camera to save images

with minimum JPEG compression ("Fine") and 1200 pixels on the vertical

--by whatever minimum horizontal resolution is available (often 1600).

If you camera can be set to save without compression --and you've purchased

lots of memory, then go that way.

* Once you transfer your images

onto your computer's hard drive and start working them, always resave

them as TIFFs, BMPs, or some other "non-lossy" 24 bit color file format.

If you keep resaving to JPEGs, your images will suffer serious degradation.

(Exception: you of course make a separate JPEG copy for use as e-mail attachments

and web page postings.)

* The first step in working a

digital pair is to open first the right, then the left frames, copying

each and placing them together into your (say) Holmes/Bates format 3.5"

x 7" card size image space (a "TIFF" image AT 300 DPI).

* When you place the right image

you'll have to reduce its size --per the displayed ruler above the card

image --and you want about 2-7/8". A good graphics program tells

you what finished percentage and/or pixel size that is --so note

that number. (That number will likely vanish when you "set" the image --write

it down.)

* When you place the left image,

first size it to the same reduction you used for the right image, then

move it over the right image in order to match it for vertical registration

(possibly selecting 50% transparency mode), THEN move it (straight!) back

over to the left and set it.

*** NOTE: If you have any intention

of outputting your stereo pair to a printed view card, be very sure to

work your pair as a TIFF image at 300 DPI and to scale (ie: sized for a

traditional Holmes/Bates 3.5" x 7" card). In that case, the header on your

graphics program's image pair window is going to indicate "1:4" (25% display

size) as you work on an 800x600 monitor, or maybe "1:2" (50%) if you're

working on a higher resolution monitor. I suggest that you work all view

pairs for a 7" card and reduce the finished pair to 71% for 5 inch wide

cards.

Also:

* If you create your pair on

a 41% gray ground, it stands a good chance of matching Crescent brand "Photo

Gray" mat board --assuming that you physically cut out and mount the pair

as chips.

Scanning In Your Old Stereo

Film

{5/14/05 update: I now use the affordable "Canoscan-8400F"

--cheaper and better than my old Olympus ES-10S --which no longer works

in an XP environment.]

It's important to get that old color print film digitized

before it fades --but it's tough to get good commercial scanning service

for 5 and 4 perforation stereo frames. Consider purchasing a film scanner

and doing it yourself.

Here follows 3 self-legended, gray scale, ES-10S test

frames for your consideration. (I removed a lot of scratches so these frames

would compress nicely.)

Like most digital imaging, the ES-10S outputs 24 bit

color --which is just enough to allow a bit of image correction and still

be able to turn out a nice print. Unlike most film scanners, its "D-range"

is vaguely described and often assumed to be only "24 bits". According

to the manual, the ES-10S uses up to 30 bits internally --but that still

doesn't address a scanner's grasp of density range --from which one may

choose about 1.5d for a 24 bit color output.

Context:

* Don't be confused by "32 bit" color imaging --which

often refers to "CMYK" printer ready images --and includes the otherwise

redundant 8 bit "K" channel.

* A D-range of 1.5d (beyond the .3d or so film base/mask)

is about it for most photographic color prints. (I've measured a 1.8 Dmax

on force-dried gloss imaging.)

* It's also about the range of color negative film

emulsions --which (accordingly) run at a gamma (or: "contrast index") of

about .5 --instead of the .7 or so for black and white emulsions.

In other words, the reach of even a humble scanner

like the ES-10S exceeds the reach of most color negative emulsions, answers

the tonal range you'd want to make a print, and can drag about the same

image out of a negative that you'd be able to produce in your darkroom.

* Black and white negative films and color reversal

films run a much deeper Dmax of up to 3d (1000-to-1) --maybe beyond for

astronomical emulsions; so the limits of the ES-10S can be important. But

again: to turn transparencies into prints, some of a slide's tonal range

often has to be compressed or thrown into black anyway.

'Bye for now,

Craig

(On to

Trim-2)